20 years Faculty of Science: the past, present and future of Psychobiology

26 May 2020

Tekst: Edda Heinsman. Fotografie: Liesbeth Dingemans

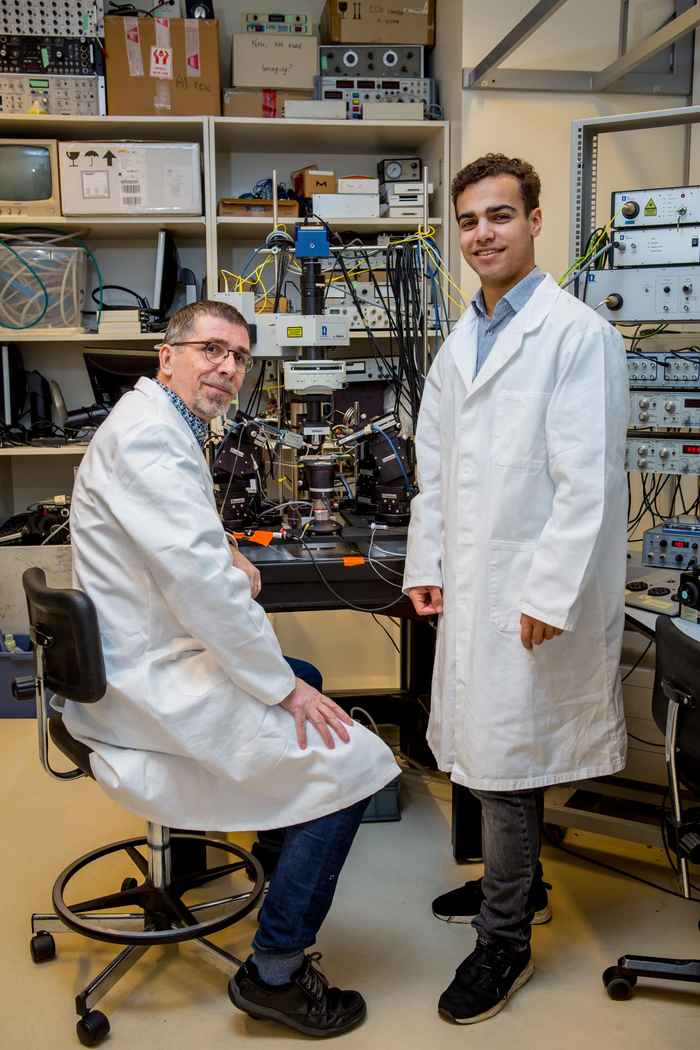

While the elephant skeleton is fun for the picture, it has little to do with the research of neurobiologist Werkman and psychobiology student Robles. So let's put on the white coats and make the rounds through the labs. That is where the magic happens: where researchers carefully and diligently conduct brain research. With top-of-the-line equipment, they can study the brain down to the smallest detail, cell by cell – and that is what psychobiology is all about: the biological mechanisms of the psyche.

'Twenty years ago, psychologists still saw the brain as a black box. They conducted research into emotion, language and behaviour, for instance, but they were ignoring the biological foundations, the processes in the brain', says Werkman. It was time for that to change. Since 2003, Werkman has been closely involved in the psychobiology Bachelor's programme, a combination of the psychology and biology fields that, in the Netherlands, is only offered at the UvA. 'However, it was a right mess at first', Werkman explains. 'The subjects were not properly coordinated, and students were still being instructed in less relevant subjects, such as botany, because we were borrowing from both programmes.' Fortunately, the situation quickly improved, and psychobiology now has its own curriculum with separate subjects, tailored to the new programme.

Psychobiology proved to be quite popular. 'The programme was immediately in demand', says Werkman. 'By 2010, we already had 400 first-year students. We were, perhaps, a bit too successful. The lecture rooms were so full that we had to stream lectures to the adjacent rooms. We were bursting at the seams, so we implemented an enrolment quota.' Robles sees the benefit in this: 'There’s an entrance test that you have to study for. This gives you an impression of the programme's content, weeding out the students who aren't truly interested.'

A very expensive razor

Let's continue the tour. We stop at a number of machines in the lab. A stereotactic device to make precise 3D measurements in tissue. Robles shows us the patch clamp set-up, which allows them to measure electricity in individual cells. He used it during a practical to look at the cells of worm brains. 'And look at this little device', Werkman says, pointing out a nondescript box the size of an old-fashioned amplifier. 'This is a very expensive razor, costing 30 thousand euros, which lets you cut very thin slices of tissue.'

Robles can barely imagine – although he does know what oscilloscopes are. They were still commonly used 20 years ago, but have long since been replaced by software on a laptop. ‘To measure the strength of a signal, now we just press a button', says Robles. 'All the data is saved on a hard drive.' Werkman: 'We saved our data by taking a Polaroid picture of the oscilloscope's screen.’

Laboratory animals

It is quiet in the lab during the tour, or we would not have been able to visit. Research is conducted on animal tissue. What is it like to do research on animals? 'With every study, we ask: does the expected result outweigh the suffering of the animal? You are constantly forced to make that consideration', says Robles. Both agree that this is a positive development. Werkman: 'Before the Experiments on Animals Act, nobody monitored how many rats were being killed. And we shouldn’t forget that the research itself also benefits from providing optimal conditions for the animals. I dare say that the animals here are a lot better off than many pets.'

Despite the growing number of alternatives, animal testing remains important, says Werkman: 'It's easy for Trump to say that he wants a coronavirus vaccine within a few months, but it really does have to be tested first, and I doubt Trump will be first in line for the tests!'

All in all, Werkman is satisfied with the state of the degree programme now. 'You see a lot of programmes that start and then disappear again after a while. I expect we'll still be around at the next anniversary of the Faculty of Science: psychobiology will stay.' Robles agrees: 'Due to the ageing of the population, attention for conditions such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's is growing. How exactly does signal transmission in the brain work? Those are exactly the kinds of brain diseases that we are researching, and we still have much to discover.'

Lees ook

- FNWI 20 jaar: Biologie toen, nu en straks

- FNWI 20 jaar: Biomedische wetenschappen toen, nu en straks

- FNWI 20 jaar: Kunstmatige Intelligentie

Twitter. Zo blijf je op de hoogte van wetenschappelijke inzichten en het laatste nieuws over FNWI.